1. Boys growing into Men

2. Transition from Boys to Men.

Accident – Death – Obituary News :

Several male students once approached my colleague to ask if he would be an advisor for a new club they were starting. The purpose? To promote manliness on campus. He declined, tartly informing them that the first thing they needed to know is that manly men do not start clubs promoting manliness.

He wasn’t entirely wrong. There is a reason the field of “gender studies” is dominated by women. This has something to do with the history of feminism, but also with the fact that women tend to be more introspective than men. No book by a man comes close to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in exploring the experience and meaning of manliness. True, there is a sizable and active “manosphere,” but its tone and content often consist of grievances, resentment, misogyny, and crude machismo stereotypes.

The Fading of Tacit Cultural Norms

For most of human history, the cultural and moral norms governing manliness were tacit and did not require much reflection. This was true as late as my own childhood in the 1970s and ’80s. The fifth of six boys (with one sister on each end), in a neighborhood filled with other rowdy and largely unsupervised boys, I learned how to fight, take risks, make friends, trust or challenge others, and negotiate and enforce rules for our games. Much of our experience was filtered through the books we read, like J. D. Fitzgerald’s extraordinary Great Brain series. And somehow, most of us looked forward to “growing up,” when we would assume the responsibilities of work, marriage, and family.

Start your day with Public Discourse Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

Yet I sympathize with the students who tried to start the manliness club. Like so much else in our “anti-culture,” the tacit script for manliness has been destroyed. American males are in a crisis, and both men and women know it. That crisis was identified as early as 2000 in The War Against Boys: How Misguided Policies Are Harming Our Young Men by Christina Hoff Sommers. It has only deepened since then, as both Leonard Sax and more recently Richard Reeves have demonstrated. Sax and Reeves highlight many of the causes for this crisis: no-fault divorce, increasing fatherlessness, the sexual revolution, radical feminism, an infantilizing entertainment culture, pornography, the “medicalization of misbehavior,” the loss of blue-collar jobs, elite contempt for manual labor, easy availability of recreational drugs, and safetyism.

These are formidable challenges. But to fully meet them we first need to know what a man is, not just an “adult male of the human species,” but a real man, a “man in full,” a gentleman. It turns out this is a most interesting question to explore—and not an easy one to answer.

The Gentleman: Historical Models

Consider the different models of men in our history and literature: Achilles and Odysseus; Aristotle and Alexander the Great; St. Francis of Assisi and Thomas More; John Wayne’s Tom Doniphon and Jimmy Stewart’s Ransom Stoddard. Is there one model of manliness here?

Perhaps it is easier to begin by identifying what a man is not. In an insightful and provocative 2004 essay entitled “Wimps and Barbarians,” Terence Moore wrote the following:

Too often among today’s young males, the extremes seem to predominate. One extreme suffers from an excess of manliness, or from misdirected and unrefined manly energies. The other suffers from a lack of manliness, a total want of manly spirit. Call them barbarians and wimps. So prevalent are these two errant types that the prescription for what ails our young males might be reduced to two simple injunctions: Don’t be a barbarian. Don’t be a wimp. What is left, ceteris paribus, will be a man.

My female students especially nod their heads at this description, though the men feel it too. But what if “wimp” and “barbarian” are, in fact, the two basic default positions of males in the absence of the right education, the spontaneous development, if you will, of latent tendencies in boys to be “babies” and “bullies”?

This seems plausible. Unlike other animals, human beings require considerable cultural investment to mature. Culture, like agriculture, does not involve dominating nature, but rather, assisting nature in its innate drive toward fruitfulness. Without the right culture, boys will become as disordered and stunted in their growth as an unpruned apple tree.

Known by Their Fruits

What is the fruit of manhood? We have a sign hanging in the bathroom for our five boys. It was inspired by a talk Jonathan Reyes gave in 2019. At the top it says “The Difference between a Boy and a Man,” and beneath it in two columns are contrasting qualities like the following: “Boys seek Comfort, Men seek a Challenge”; “Boys Complain, Men Endure”; “Boys have Bros, Men have Friends;” and (one of my own additions) “Boys break Things, Men make Things.”

The sign has given focus to our parenting and clarity to our sons. It has also generated constructive and often amusing conversations with guests. The truth in the descriptions and contrasts is evident to anyone who has spent time working with boys, whether as a parent, teacher, or coach. The task is clear. The challenge is: how?

Plato in his Republic is the first thinker to observe natural male tendencies toward what Moore calls “wimpiness” (undue softness) on one hand, and “barbarism” (undue aggressiveness) on the other. He offers an education to shape, direct, and harmonize these tendencies. His goal is to transform natural babies and bullies into “beautiful and good men” (kalosk’agathoi), or gentlemen. This education consists of two parts, what he calls “music” and “gymnastic.” Plato’s understanding of these terms is broader and deeper than ours today.

Music is the first and most fundamental part of education because human beings, especially children, are deeply mimetic. They respond to stories more than rational discourses and measure themselves by concrete models more than abstract principles. It is thus imperative that from a young age, boys hear the right stories, especially about God, heroes, and ordinary human beings. But Plato is also concerned with how the stories are told, “Because rhythm and harmony most of all insinuate themselves into the inmost part of the soul and most vigorously lay hold of it in bringing grace with them; and they make a man graceful if he is correctly reared, if not, the opposite.” Plato makes clear that the goal of the music education is not to compete with reason, but to cultivate it:

And due to his having the right kind of dislikes, he would praise the fine things; and, taking pleasure in them and receiving them into his soul, he would be reared on them and become a gentleman [kalosk’agathos]. He would blame and hate the ugly in the right way while he is still young, before he is able to grasp reasonable speech. And when reasonable speech comes, the man who is reared in this way would take the most delight in it, recognizing it on account of its being akin. (Emphasis added.)

It is no accident that C. S. Lewis appeals to this very same passage in The Abolition of Man. In putting poetry before philosophy and highlighting the deeply aesthetic dimension of reason, Plato helps correct a distinctively modern and rationalist conception of reason as critical, detached, and dispassionate. Music education, which forms what Edmund Burke called the “moral imagination,” directs erotic desire beyond the merely useful and pleasurable goods to the ennobling “beautiful goods” (kala/honesta bona)—goods for their own sake, like friendship and knowledge.

As to the gymnastic education, Plato is less detailed, but he makes it clear that the principal goal is not bodily fitness. To the contrary, Plato warns his readers against an undue preoccupation with bodily health in a way that seems written for our own age, in which the fear of aging and obsession with health drive a multibillion-dollar industry in untested dietary supplements, organic foods, and novel exercise regimens. He singles out for criticism a certain Herodicus, a “gymnastic master” who became “sickly” and “drew out his death.” “Attending the mortal disease,” Plato writes:

he wasn’t able to cure it . . . and spent his whole life treating it with no leisure for anything else, mightily distressed if he departed a bit from his accustomed regimen. So, finding it hard to die, thanks to his wisdom, he came to an old age.

For Plato, the purpose of the gymnastic education is to train the soul in courage. To him, this means avoiding the “idleness” and “licentiousness” that are the main sources of bodily ailments and prevent the soul from pursuing the beautiful goods that are the ultimate objects of human desire.

1. Boys to Men public discourse

2. Boys to Men societal discussion.

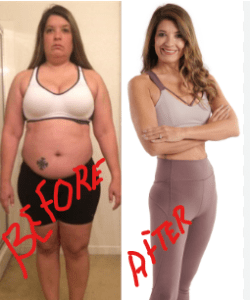

A Teaspoon Before Bedtime Makes you Lose 32LBS in 2 Weeks.

Related Post : Remember Tiger Wood's Ex Wife, Elin Nordegren ? Take a Look at Her Now.

The Conjoined Twins Abby & Brittany Hensel are No Longer Together.